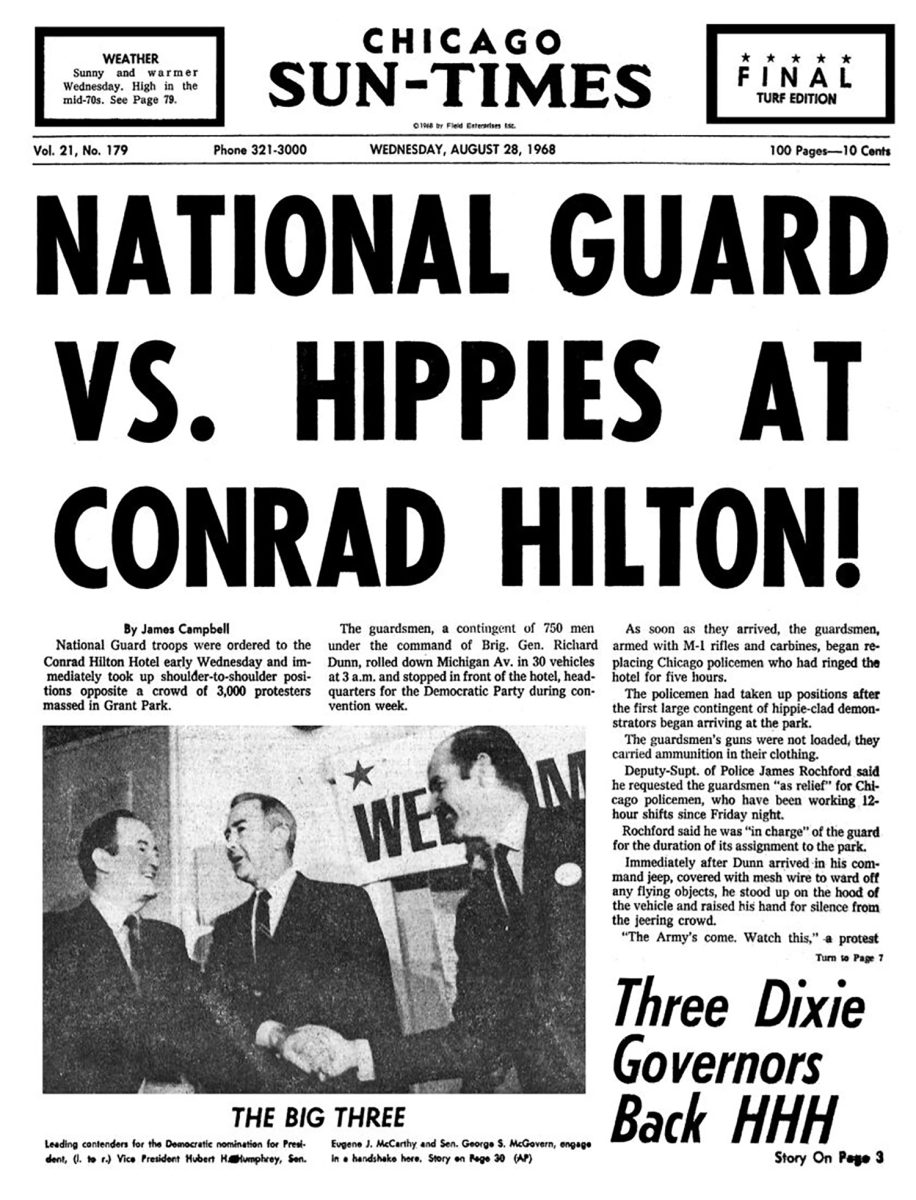

Some 56 years ago, the 1968 Democratic National Convention was held Aug. 26-29 at the International Amphitheatre in Chicago. Earlier that year, incumbent President Lyndon B. Johnson had announced he would not seek reelection, thus making the purpose of the convention to select a new presidential nominee for the Democratic Party.

Who says history doesn’t repeat itself?

The most contentious issues of the 1968 convention were the continuing American military involvement in the Vietnam War and voting reform expanding the right to vote for draft-age soldiers who were unable to vote because the voting age was 21.

The Democratic Party was divided when Sen. Eugene McCarthy entered the campaign in November 1967, challenging incumbent President Johnson for the Democratic nomination. Sen. Robert F. Kennedy tossed his hat in the ring in March 1968.

The ’68 convention was held during a year of riots, political turbulence and mass civil unrest. The assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. in April of that year was followed by riots in more than 100 cities. The convention also followed the assassination of Robert F. Kennedy on June 5, further derailing the convention and paving the way for Vice President Hubert Humphrey, a pro-war candidate.Johnson, facing dissent within his party, announced on March 31 that he would not seek re-election.

In his television address announcing his withdrawal from the presidential race, Johnson also announced that the United States would stop bombing North Vietnam north of the 19th parallel and was willing to open peace talks.

In his television address announcing his withdrawal from the presidential race, Johnson also announced that the United States would stop bombing North Vietnam north of the 19th parallel and was willing to open peace talks.

On April 27, Humphrey entered into the race but did not compete in any primaries; instead, he inherited the delegates previously pledged to Johnson and then collected delegates in caucus states, especially in caucuses controlled by local Democratic bosses.

Peace talks had begun in Paris but almost immediately became deadlocked as the head of the North Vietnamese delegation demanded the U.S. give a promise to unconditionally stop bombing North Vietnam, a demand rejected by W. Averell Harriman of the American delegation.

The ’68 convention was among the most tense and confrontational ever in American history. The convention’s host, Mayor Richard J. Daley of Chicago, had refused permission for “anti-patriotic” groups to demonstrate and had the International Amphitheatre, where the convention was being held, ringed with barbed wire while putting the 11,000 officers of the Chicago Police Department on 12-hour shifts. In addition, there were 6,000 armed men from the Illinois National Guard called up to guard the amphitheater, giving the feeling that Chicago was a city under siege.

Daley ruled Chicago in an extremely authoritarian style and felt very strongly that any protesters were going to ruin what was supposed to be his moment of triumph and was determined to stop them.

When the media reported that Daley had given orders to the police to restrict the activities of Democratic delegates loyal to peace candidate McCarthy, Daley was enraged, giving a rambling press conference saying, “This is a vicious attack on this city and its mayor.”

The leaders of the Yippies (Youth International Party), Abbie Hoffman and Jerry Rubin, specialized in outlandish, bizarre rhetoric that attracted maximum media attention, and Daley took many of their more outrageous threats seriously.

Daley’s heavy-handed security measures incensed the media. CBS anchor Walter Cronkite complained of … “a totally unwarranted restriction of free and rapid access to information.”

CBS commentator Eric Sevareid said Chicago “runs the city of Prague, (which at that time was under Soviet control) a close second right now as the world’s least attractive tourist destination.” Undercover agents had infiltrated the protesters, including agents from the Central Intelligence Agency, who, contrary to U.S. law, had been sent to spy upon American citizens.

In late August, more than 10,000 people had arrived in Chicago to protest the Vietnam War. The Chicago police raided the mostly Black neighborhoods of South Chicago to stage mass arrests of the Blackstone Rangers, a black Power group that was alleged to be planning to assassinate Vice President Humphrey.

At the convention itself, tensions were much evident between pro-war and anti-war Democrats. The more “dovish” Democrats favored accepting the North Vietnamese demand while more “hawkish” Democrats demanded the North Vietnamese promise not to send any men down the “Ho Chi Minh Trail” as their precondition for a bombing pause, a demand the North Vietnamese rejected.

Complicating the 1968 election was the third-party candidacy of Alabama Gov. George Wallace, who ran on a white supremacist platform promising to undo all of the changes brought by the 1964 Civil Rights Movement.

President Johnson distrusted Vice President Humphrey and had the FBI illegally tap his telephones to find out what he was planning to do. At the same time, though Johnson had announced he had dropped out of the election, he sent his friend John Connally, the governor of Texas, to meet with other Democratic governors of Southern states attending the convention to inquire if they would be willing to support nominating Johnson to be the Democratic candidate after all.

It remains unclear if Johnson was serious about re-entering the presidential race, or if he was merely using the prospect of running again as a way to keep Humphrey from straying too far from his Vietnam policies. Regardless of what Johnson was intending, Connally had to tell his fellow Texan that the general feeling about Johnson being the Democratic candidate in 1968 was: “No way!”

The security measures imposed by Daley had been so intense that it was not possible to walk across the convention floor without jostling other delegates, which added to the tensions as “dovish” and “hawkish” Democrats fiercely argued about whether to accept Johnson’s war plank to the platform. All of it was captured live on national television.

In the end, the Democratic Party nominated Humphrey, who had not entered any of the 13 state primary elections.

The nomination was watched by 89 million Americans. The three major networks, CBS, NBC, and ABC, broadcast live the so-called “Battle of Michigan Avenue,” which was taking place in front of the Conrad Hilton Hotel in downtown Chicago. The police sprayed demonstrators and bystanders with mace. Police indiscriminately attacked all who were present, whether involved in the demonstrations or not.

The election of 1968 was one of the closest ever in American history, with Nixon winning 31.7 million votes, Humphrey 31.2 million votes and Wallace a few more than 10 million votes. Compared to the 1968 convention, with its many similarities, the 2024 convention in Chicago was relatively calm. To be sure, no matter how it’s read, the year 1968 was a dark time in our American history.

Tom Morrow is a longtime Oceanside-based journalist and author.

Columns represent the views of the individual writer and do not necessarily reflect those of the North Coast Current’s ownership or management.