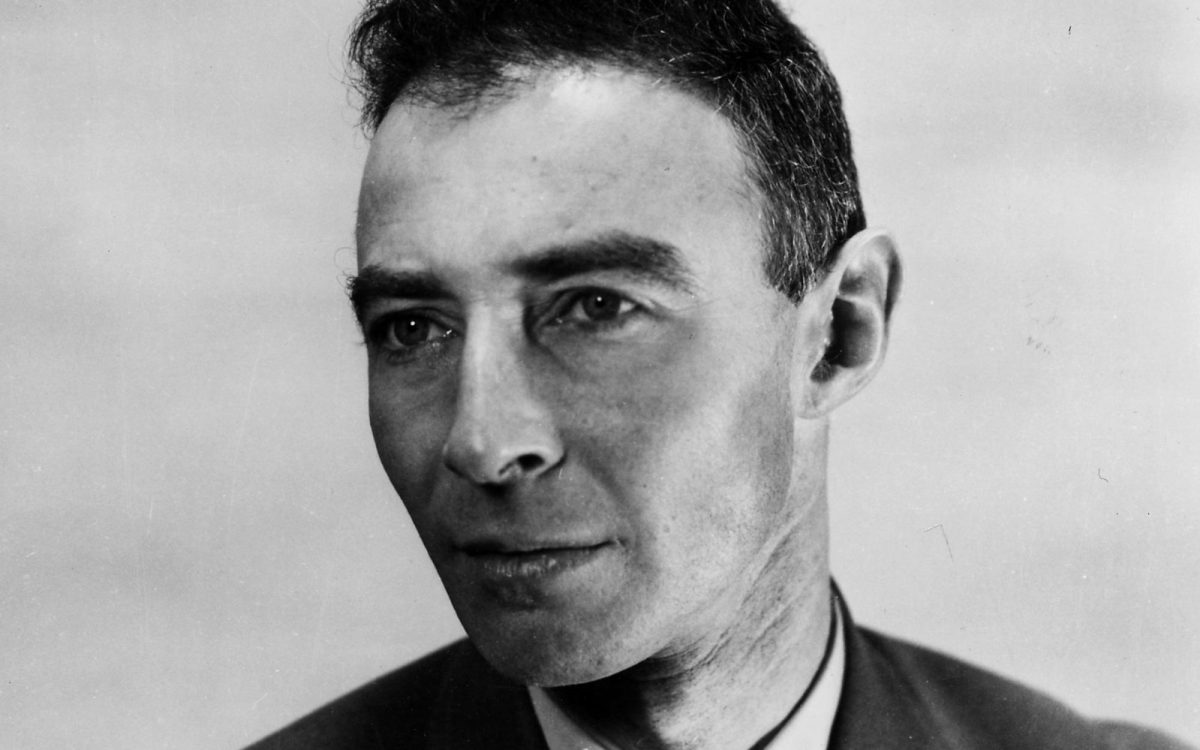

After more than a half century nearly forgotten in history books, the name of Julius Robert Oppenheimer, primarily responsible for the development of the atomic bomb, has been reintroduced to the public by way of a big-screen Hollywood film.

Oppenheimer, a nuclear physicist, arguably was one of history’s most controversial figures. Some historians list him as being the savior from world conflicts, while others regard his work as that of the devil, forever plaguing the planet to instant destruction.

Born April 22, 1904, Oppenheimer was director of the highly secret Los Alamos Laboratory during World War II. He is credited as being the “father of the atomic bomb” for his leadership in creating the first nuclear weapons.

Not only was he controversial for his role in the development of atomic energy, Oppenheimer also was suspected of having communist leanings. Though he never openly joined the Communist Party, he did pass money to leftist causes by way of acquaintances who were alleged to be party members. Various associations Oppenheimer had with people and organizations affiliated with the Communist Party led to the revocation of his security clearance in 1954.

On October 9, 1941, two months before the United States entered World War II, President Franklin D. Roosevelt approved a crash program to develop an atomic bomb. In June 1942, the U.S. Army established the Manhattan Engineer District to handle its part in the atom bomb project. Brig. Gen. Leslie Groves was appointed director of what became known as the Manhattan Project. He selected Oppenheimer to head the project’s secret weapons laboratory.

On October 9, 1941, two months before the United States entered World War II, President Franklin D. Roosevelt approved a crash program to develop an atomic bomb. In June 1942, the U.S. Army established the Manhattan Engineer District to handle its part in the atom bomb project. Brig. Gen. Leslie Groves was appointed director of what became known as the Manhattan Project. He selected Oppenheimer to head the project’s secret weapons laboratory.

This choice surprised many because of Oppenheimer’s left-wing political views and having no record of being a leader of large projects. Groves was impressed by Oppenheimer’s singular grasp of the practical aspects of designing and constructing an atomic bomb. As a military engineer, Groves knew this would be vital in an interdisciplinary project that would involve not just physics, but chemistry, metallurgy, ordnance and engineering.

Groves also detected in Oppenheimer something many others did not: overwhelming ambition. Groves reckoned that quality would supply the drive necessary to push the project to a successful conclusion. Fellow scientist Isidor Rabi considered Oppenheimer’s appointment a stroke of genius on the part of Groves, who was not generally considered to be an “intellect.”

Oppenheimer and Groves decided for security and cohesion that they needed a centralized, secret research laboratory in a remote location. They selected a spot in northern New Mexico not far from the scientist’s ranch. The Los Alamos Laboratory was built on the site of a boys’ school, taking over some of its buildings, while many new buildings were quickly constructed.

Los Alamos was initially supposed to be a military laboratory, and Oppenheimer and other researchers were to be commissioned into the Army. But some of the scientists balked at the idea, so Groves and Oppenheimer compromised whereby the laboratory would be operated by the University of California under contract to the War Department.

Oppenheimer had underestimated the magnitude of the project as Los Alamos grew from a few hundred people in 1943 to more than 6,000 in 1945.

In 1943, there was anxiety among the U.S. scientists that the Germans might be making better progress on an atomic weapon than they were. Oppenheimer discarded a proposal to use radioactive materials to poison German food supplies. Oppenheimer questioned whether enough strontium could be produced without letting too many in on the secret. In a letter, he wrote: “I think we should not attempt such a plan unless we can poison food sufficient to kill a half a million men.”

The joint work of the scientists at Los Alamos resulted in the world’s first nuclear explosion, near Alamogordo, New Mexico, on July 16, 1945. Oppenheimer had given the site the codename Trinity. Years later, he said a verse entered his head at that time, translated as: “I have become death, the destroyer of worlds.”

Among those present with Oppenheimer in the control bunker at the Trinity site were his brother Frank and Brig. Gen. Thomas Farrell. When Frank Oppenheimer was asked what Robert’s first words after the test had been, the answer was, “I guess it worked.”

A month later, atomic bombs were dropped on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, which brought about the end of World War II. The public was not aware of the “Top Secret” Manhattan Project until after the war. By 1946, the public was made aware of secret U.S. atomic bomb plans being passed by Russian spies, which resulted in the Soviet Union becoming a nuclear power.

In October 1945, Oppenheimer was granted an interview with President Harry S. Truman, who was not made aware of the Manhattan Project until he became president upon Roosevelt’s death in April 1945. Oppenheimer told Truman that he felt as though he had “blood on my hands.” The remark infuriated Truman, who quickly ended their meeting. Truman later told Undersecretary of State Dean Acheson, “I don’t want to see that son-of-a-bitch in this office ever again.”

After the war, Oppenheimer became chairman of the newly created U.S. Atomic Energy Commission. He lobbied for international control of atomic power to avert a nuclear race with the Soviet Union.

At his 1954 security clearance hearings, he flatly denied being a member of the Communist Party but did identify himself as a “fellow traveler,” which he defined as “someone who agrees with many of communism’s goals but is not willing to blindly follow orders from any Communist Party apparatus.” Oppenheimer was stripped of his security clearance.

He died Feb. 18, 1967, at the age of 62.

The recently released biopic, “Oppenheimer,” is now showing in theaters.

Tom Morrow is a longtime Oceanside-based journalist and author.

Columns represent the views of the individual writer and do not necessarily reflect those of the North Coast Current’s ownership or management.