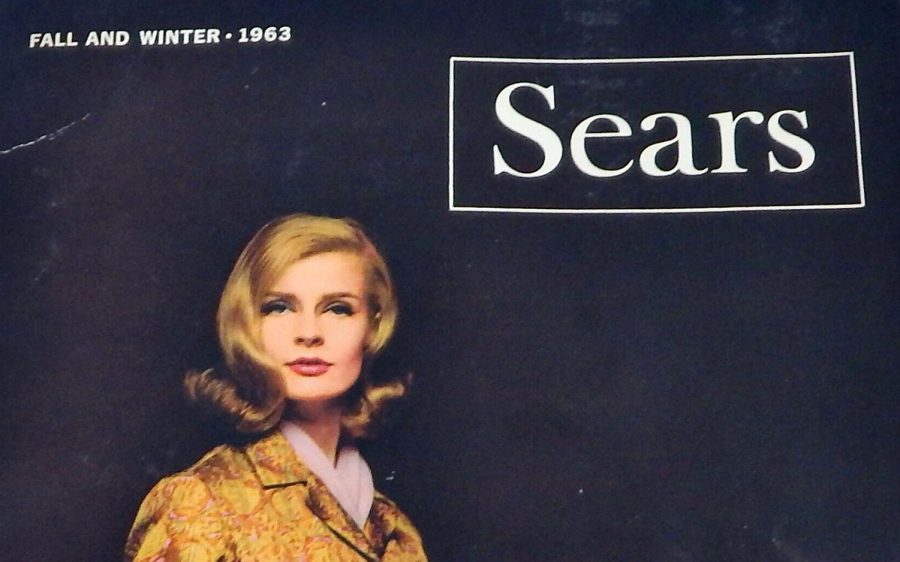

Historically Speaking: The nation’s first mail order general stores

May 10, 2023

Since 1875, anyone living on the North American continent could buy nearly anything from a pair of shoes to a house kit. Before there were roads connecting the Atlantic to the Pacific and Mexico to Alaska, you could buy goods delivered via railroad freight and/or the U.S. mail. This was more than a century before the Internet, all courtesy of the mail-order catalogs of the Montgomery Ward and Sears & Roebuck companies. It was the Amazon of yesteryear.

The concept of mail order for delivery via freight or mail purchases was the revolutionary idea of Aaron Montgomery Ward, who was born Feb. 17, 1843. He began his revolutionary retailing concept in 1875. The business plan was copied in 1892 by Richard Warren Sears, who was born Dec. 7, 1863. Later, Alvah Curtis Roebuck, born Jan. 9, 1864, joined Sears.

Ward worked at a country store, where he learned the retail business. Although, in 1873, his idea was generally considered lunacy by his friends. Ward proceeded to put his plan into operation, but his first inventory was destroyed by the Great Chicago Fire. Ward persevered and regrouped with a total capital of $1,600. Forming the Montgomery Ward company, Ward rented a small shipping room in Chicago and began publishing a mail-order catalog listing 163 general merchandise products.

Ward worked at a country store, where he learned the retail business. Although, in 1873, his idea was generally considered lunacy by his friends. Ward proceeded to put his plan into operation, but his first inventory was destroyed by the Great Chicago Fire. Ward persevered and regrouped with a total capital of $1,600. Forming the Montgomery Ward company, Ward rented a small shipping room in Chicago and began publishing a mail-order catalog listing 163 general merchandise products.

Soon, Ward’s catalog caused controversy among rural general store retailers and was even burned publicly. But those early catalogs became known as the “wish book,” becoming a favorite in households across America.

Sears mailed his first catalog in 1896. He believed cutting the costs and making a wide variety of goods available to rural customers would be well received. Sears became popular for his motto: “Satisfaction guaranteed or your money back.”

In 1886, Sears purchased dozens of inexpensive watches, then sold them at a low price primarily to railroad station agents. He started a mail-order watch business in Minneapolis in 1886, calling it “R.W. Sears Watch Company.” Within the first year, he met Alvah C. Roebuck, a watch repairman, and in 1887, together Sears and Roebuck relocated their business to Chicago.

Sears’ first catalog just offered watches, diamonds and jewelry. In 1893, they renamed the company to Sears, Roebuck & Co. and expanded their product lines.

By the turn of the century, both Chicago-based mail-order companies were sending tens of thousands catalogs to homes and businesses from Mexico to the far reaches of Canada and Alaska. For remote ranches, farms and communities, the yearly catalogs offered thousands of items from clothes to farm machinery, and from 1908 to 1940, houses you could self-assemble. Hundreds of Sears homes are still in use today across America, especially in small Midwest and Western communities.

The “wish books” served not only as a buying guide for residents in rural America, they also provided additional important uses. When the newest book arrived, the old one often was used as toilet paper.

By 1895, Sears was producing a 532-page catalog. Sales were greater than $400,000 a year. By 1896, children’s dolls, cooking and heating stoves, even groceries, had been added to their catalog.

In the year 1900, Sears, Roebuck lost annual revenue. Ward had total sales of $8.7 million, compared with $10 million for Sears. Both companies struggled for dominance during much of the 20th century. By 1904, Ward’s company was mailing some 3 million catalogs, each weighing around 4 pounds.

In 1908, Ward opened a 1.25-million-square-foot mail-order building stretching along nearly one-quarter mile of the Chicago River.

The Sears catalog became known in the industry as “the Consumers’ Bible.” Rural African-Americans, especially in areas dominated by Jim Crow racial segregation, deemed Sears and Ward catalogs vital retail alternatives to local white-dominated stores, bypassing the merchants’ frequent efforts to deny fair access to their merchandise.

In 1978, the Ward catalog house was declared a National Historic Landmark. Up to the 1980s, Sears was the largest retailer in the United States. But by 1990, Walmart surpassed both Sears and Ward in sales, dropping Sears to the nation’s 31st-largest retailer before falling into bankruptcy. Ward experienced the same fate.

For Sears, the cost of distributing the general merchandise catalog became prohibitive; sales and profits had declined. In 1993, Sears discontinued publishing the book, dismissing 50,000 workers who had filled mail orders.

Sears, Roebuck and Ward were the pioneers in modern retailing. Amazon.com has merely perfected their system.

Tom Morrow is a longtime Oceanside-based journalist and author.

Columns represent the views of the individual writer and do not necessarily reflect those of the North Coast Current’s ownership or management.