Historically Speaking: The banker who saved America

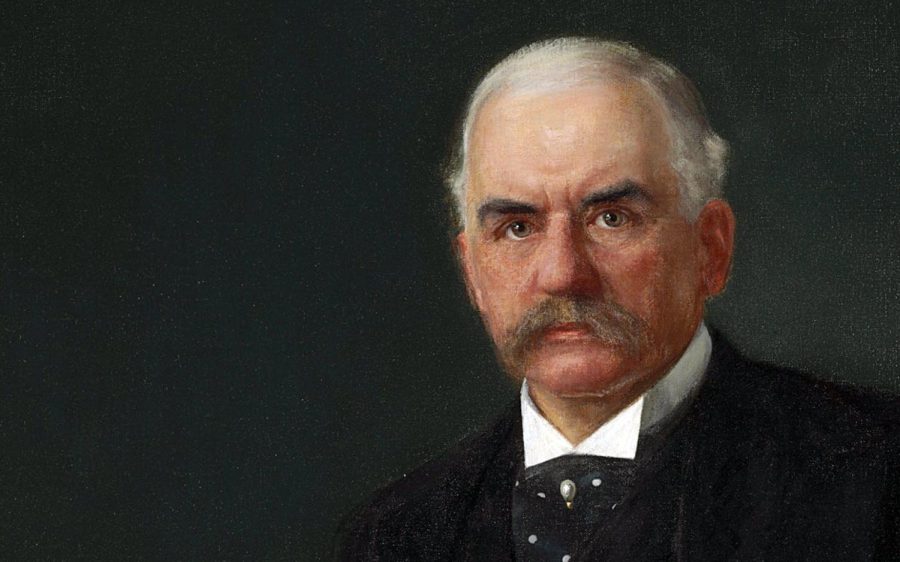

A portrait of American financier John Pierpont (J.P.) Morgan, painted by Fedor Encke in 1903. (Creative Commons image)

March 22, 2023

One of the important financial entrepreneurs of the 19th century who was key to building America was John Pierpont Morgan. The New York financier not only orchestrated the federal government’s vast financial system, he created several huge corporations that became the center of the U.S. manufacturing world. In lieu of today’s current financial climate in Washington, D.C., reviewing a bit of national banking history seems to be in order.

John Pierpont Morgan Sr., born April 17, 1837, was a banker who dominated corporate finance and industrial consolidation in the United States during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

When the nation’s banking system was in a shaky, chaotic condition, Morgan played a key role in America’s financial reorganization as well as the formation of such well-known giants as General Electric, U.S. Steel, International Harvester and communications conglomerates such American Telephone & Telegraph (AT&T).

During the early part of the 20th century at the height of Morgan’s career, he and his partners had financial investments in many large corporations and had significant influence over the nation’s high finance as well as U.S. presidents and members of Congress. He directed the banking coalitions that stopped the national financial Panic of 1907; was the leading financier of the so-called Progressive Era, and his dedication to efficiency and modernization helped transform much of today’s American business. Yet, he was dubbed a “robber baron” because he profited in the collapse of earlier businesses such as Westinghouse.

During the early part of the 20th century at the height of Morgan’s career, he and his partners had financial investments in many large corporations and had significant influence over the nation’s high finance as well as U.S. presidents and members of Congress. He directed the banking coalitions that stopped the national financial Panic of 1907; was the leading financier of the so-called Progressive Era, and his dedication to efficiency and modernization helped transform much of today’s American business. Yet, he was dubbed a “robber baron” because he profited in the collapse of earlier businesses such as Westinghouse.

Morgan learned at an early age how to make money. At 26, during the Civil War, in an incident known as the Hall Carbine Affair, Morgan financed the purchase of 5,000 rifles from a U.S. Army arsenal at $3.50 each, which he then resold to an Army field general for $22 each.

Morgan’s process of taking over troubled businesses to reorganize them became known as “Morganizations.” He reorganized businesses in order to return them to profitability. Morgan’s reputation as a banker and financier also helped bring interest from investors to the many businesses he had taken over.

At the depths of the Panic of 1893, by 1895, the Federal Treasury was nearly out of gold. Morgan had put forward a plan for the federal government to buy gold from his European banks. Morgan came up with a plan to use an old Civil War law allowing him to sell 3.5 million ounces of gold directly to the U.S. Treasury, restoring the nation’s financial surplus in exchange for a 30-year bond issue.

The episode saved the U.S., and to maintain the status quo in business, Morgan, steel magnate Andrew Carnegie, and railroad mogul John D. Rockefeller, along with some Wall Street bankers, donated heavily to Republican candidate William McKinley, who was elected in 1896 and re-elected again in 1900.

By 1900, Morgan’s financial firm was one of the most powerful banking houses in the world, focused especially on reorganizations and consolidations.

After financing the creation of the Federal Steel Company, Morgan merged it in 1901 with the Carnegie Steel Company and several other steel and iron businesses to form the giant United States Steel Corporation.

The Panic of 1907 was a financial crisis that almost crippled the American economy. Major New York banks were on the verge of bankruptcy and there was no mechanism to rescue them until Morgan stepped in to help resolve the crisis. Treasury Secretary George B. Cortelyou earmarked $35 million of federal money to deposit in New York banks. Morgan then met with the nation’s leading financiers in his New York mansion, where he forced them to devise a plan to meet the crisis.

Morgan organized a team of bank and trust executives that redirected money between banks, secured further international lines of credit, and bought up the plummeting stocks of healthy corporations.

In 1913, realizing that in a future national crisis there would unlikely to be another J.P. Morgan for a rescue, banking and political leaders devised a plan that resulted in the creation of today’s Federal Reserve System. But a similar crisis occurred 100 years later. In 2008, the J.P. Morgan-Chase bank emerged as one of the world’s largest banks, but that particular financial catastrophe, which saw the downfall of Lehman Brothers investment group, proved that no bank is “too large to fail.”

On March 31, 1913, J.P. Morgan died in Rome, Italy, at the age of 75. He left his fortune to his namesake, John Pierpont Morgan , Jr. The Morgan senior was estimated to have left a fortune at “only” $80 million, which prompted fellow so-called “Robber Baron” John D. Rockefeller to say: “… and to think, he wasn’t even a rich man.”

The 19th century “robber barons” included Morgan, oil giant John D. Rockefeller, auto builder Henry Ford, steel magnate Andrew Carnegie and railroad mogul Cornelius (the Commodore) Vanderbilt. Together, these men truly did financially and industrially build America with Morgan providing the necessary financial and organizational “glue” that held many of the nation’s key conglomerates together.

Today, as it was yesterday, there always seems to be light at the end of a very long financial-ladened tunnel.

Tom Morrow is a longtime Oceanside-based journalist and author.

Columns represent the views of the individual writer and do not necessarily reflect those of the North Coast Current’s ownership or management.