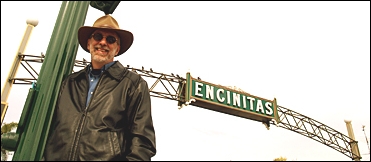

Mark Freeman is an active Encinitas-based filmmaker, but you won’t find his screenings at your local movie theater. Freeman, a San Diego State film professor, is an independent documentary filmmaker specializing in political or cultural issues, or community portraits. Each film or video he makes is different — each tells its own story. Themes he covers include stories of self-sufficiency, entrepreneurs and rural communities.

“What I really want to do is make those important stories into film that don’t get past the gatekeeper, the make-or-break media; I want to make them available,” Freeman said.

He likens his work with that of being a translator; he seeks grass roots stories, social-cause oriented ones he believes larger audiences will want to hear. His work is all about making those stories interesting, available and accessible to people who otherwise wouldn’t have the opportunity to hear them.

Freeman himself is a one-man show when it comes to making his documentaries. He writes, produces and edits his handmade films. He explains that access and resources are the two necessary items for making a documentary.

With more than 25 years of experience as a filmmaker, he has won prestigious specialty awards. His films screen at museums, at the Smithsonian and others, and are in libraries and universities throughout the country.

What drives Freeman’s passion for filmmaking?

“It’s a wonderful opportunity to participate in people’s lives in a way not possible any other way, sort of like being a journalist,” he said.

“It’s really an opportunity to assert myself into someone’s life and say, ‘I find your story interesting, and I’d like to tell more people about it.

“You have this free pass to investigate anything that you’re curious about,” Freeman said.

And curious Freeman is as he profiles ordinary individuals making a difference in their communities.

“Each of my documentaries captures a moment in our shared social history, a fragment of our collective memory in a time of complex challenges and rapid change,” Freeman states on his website.

His domestic films and videos feature subjects like Humboldt County redwood forest timber workers (“Mad River: Hard Times,” 1982); Jewish people and Palestinians dialoguing and peacemaking in San Diego (“Talking Peace,” 2005); the contribution of New Mexico’s diverse cultures to the state’s adobe architectural heritage, (“Down to Earth, 1994); and a mother who lost her son to gun violence and took action creating a movement with other mothers to reform gun laws (“One in a Million,” 2001).

Freeman has worked overseas in Mexico, Guatemala, Argentina, Ecuador, Costa Rica, Cuba and Israel. His international films and videos feature subjects like 19th century Jewish immigration to Argentina, where many became ranchers and farmers; also, indigenous weavers in the highlands of Ecuador.

Freeman is from Chicago but has lived in Encinitas since June 2000. He is a graduate of the San Francisco Art Institute, with bachelor’s and master’s degrees. Freeman treasures much here, beginning with close proximity to Beacon’s Beach, just a 15-minute walk from home. He enjoys the independent, single-screened La Paloma Theatre, and downtown Encinitas and the art scene. Freeman loves the weather here, a positive change from growing up in the cold Midwest. His teenage daughters, Ana and Miriam, attend local schools, La Costa Canyon High School and Diegueño Middle School.

Freeman has made films specifically about Encinitas. One is about a local news hawker, a homeless man whom customers appreciate. Another is an interview film portrait of Kirk Van Allyn, an environmental, or tidal, artist drawing labyrinths in the sand at the beach. Still another is about the effects of the real estate market upon the local flower industry.

Freeman also teaches documentary production and related courses at San Diego State University, where he is a tenured associate professor in the School of Theater, Television and Film. He encourages his production students to choose subjects they’re passionate about and would find worthy of the time required for crafting into film. He’s traveled with students abroad, too, to work with them on documentaries.

Freeman is excited about his current work. He’s done recent presentations in town, such as at the downtown San Diego Public Library. In the fall, for KPBS, he will have another film out abut living artists, specifically the trolley dances directed by Jean Isaacs, on the East Village trolley line.

Freeman’s most recent film is “Poetry Live(s),” pronounced according to whether it’s a noun or a verb. This is the fourth documentary he’s made in Encinitas, about spoken word poets in San Diego — it aired on KPBS on April 25 at 10: 30 p.m. The focus is on an invitational spoken word poetry slam held at the La Paloma Theatre.

Freeman’s intent is to capture the spirit and energy of the poems being presented—by using black-and-white footage, backwards footage, clips of old educational films from the 1940s and 1950s, and hand-held camera. Robert Nanninga, a local and very active spoken word poet and emcee of the slam, was very instrumental in helping Freeman gain access to the slam, introducing him to the poets, and assisting him in filming preparations. A film study of spoken word poetry fits right in with Freeman’s documentary studies of living artists.

Robert Nanninga and Spoken Word Poetry

What, exactly, is spoken word poetry? Bob Nanninga — slam emcee, a Full Moon Poet, an E Street Café manager, a weekly columnist for the Coast News, an instructor in school theater programs for children, and involved in environmental organizations — said spoken word poetry is recited before a gathered audience; it’s live presentation.

“The spoken word is much more dynamic than poetry read aloud; it’s much more 20th century, performance poetry,” Nanninga said.

It isn’t acting, per se, but it’s entertaining. The spoken word poet uses inflection and body movement in such a way as to convey the poem’s meaning. Spoken word slams at the La Paloma Theatre are competitions, with cash prizes collected in a popcorn bucket from the audience, and the proceeds going to the top three winning poets.

Such poets of Encinitas found a need 10 years ago to organize and form the Full Moon Poets, started by Danny Salzhandler. The (highway) 101 Artists’ Colony did the first poetry slam in Encinitas. It was a kind of co-op for artists, started at a storefront, and supported by the Downtown Encinitas MainStreet Association. Later, the slams would be held at the historic La Paloma Theatre, to help build a full audience. Each year, there are summer and winter slams at the La Paloma.

Nanninga said he believes spoken word poets contribute much to society. They perform original material. Nanninga has a book in progress; he writes in his style of “Nursery Crimes.” In their time, nursery rhymes were morality stories for children. Use of rhythm, wit and word play are essential to Nanninga’s performance. Working off of nursery rhymes helps him “find the rhythm” in his head. He plays the part of Father Goose, reading from a big book placed in front of him, on a counterpart with Mother Goose.

“By promoting spoken word and literacy as a writer, I enjoy a smart audience,” he said. “Every time I go on stage and work the word, I’m actually encouraging literacy, encouraging people to use their language.”

Nanninga merges his poetry and politics together, stressing planet ecology. He advises those wanting to get started in spoken word poetry to find a message and then a voice, something to say, to teach, to share with others.